1440: “Start of the Cuban Missile Crisis”

Interesting Things with JC #1440: “Start of the Cuban Missile Crisis” – A single flight over Cuba revealed the weapons that nearly ended the world. Thirteen days, two superpowers, one narrow escape from nuclear war. How reason and restraint kept humanity alive.

Curriculum - Episode Anchor

Episode Title: Start of the Cuban Missile Crisis

Episode Number: 1440

Host: JC

Audience: Grades 9–12, college intro, homeschool, lifelong learners

Subject Area: History, Government, International Relations, Civics

Lesson Overview

Students will:

Define key terms such as "quarantine," "ballistic missile," and "nuclear deterrence" in Cold War context.

Compare the missile placements in Cuba and Turkey to analyze geopolitical strategy.

Analyze the decision-making process of U.S. and Soviet leadership during the 13-day crisis.

Explain how the Cuban Missile Crisis shaped future U.S. foreign policy and nuclear diplomacy.

Key Vocabulary

Reconnaissance (ruh-KON-uh-suhns) — A U-2 reconnaissance flight over Cuba revealed Soviet missile activity.

Ballistic Missile (buh-LIS-tik MIS-uhl) — A weapon that follows a trajectory to deliver warheads; the Soviet R-12s discovered in Cuba had a range of 1,200 miles.

Quarantine (KWOR-uhn-teen) — The U.S. imposed a naval “quarantine” to avoid legal definitions of war while blocking Soviet ships.

ExComm (EX-kom) — The Executive Committee of the National Security Council that advised President Kennedy during the crisis.

Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) — An implied doctrine during the Cold War, where both sides possessed enough nuclear capability to destroy one another.

Narrative Core (Based on the PSF – Renamed Labels)

Open: A quiet island view from 70,000 feet hides a secret that could have ended the world.

Info: Soviet missiles were secretly installed in Cuba, provoking a crisis with the U.S.

Details: Kennedy formed ExComm, navigated two conflicting Soviet messages, and used diplomacy and military readiness to avoid war.

Reflection: One mother’s hope for her children underlines the humanity behind global politics.

Closing: These are interesting things, with JC.

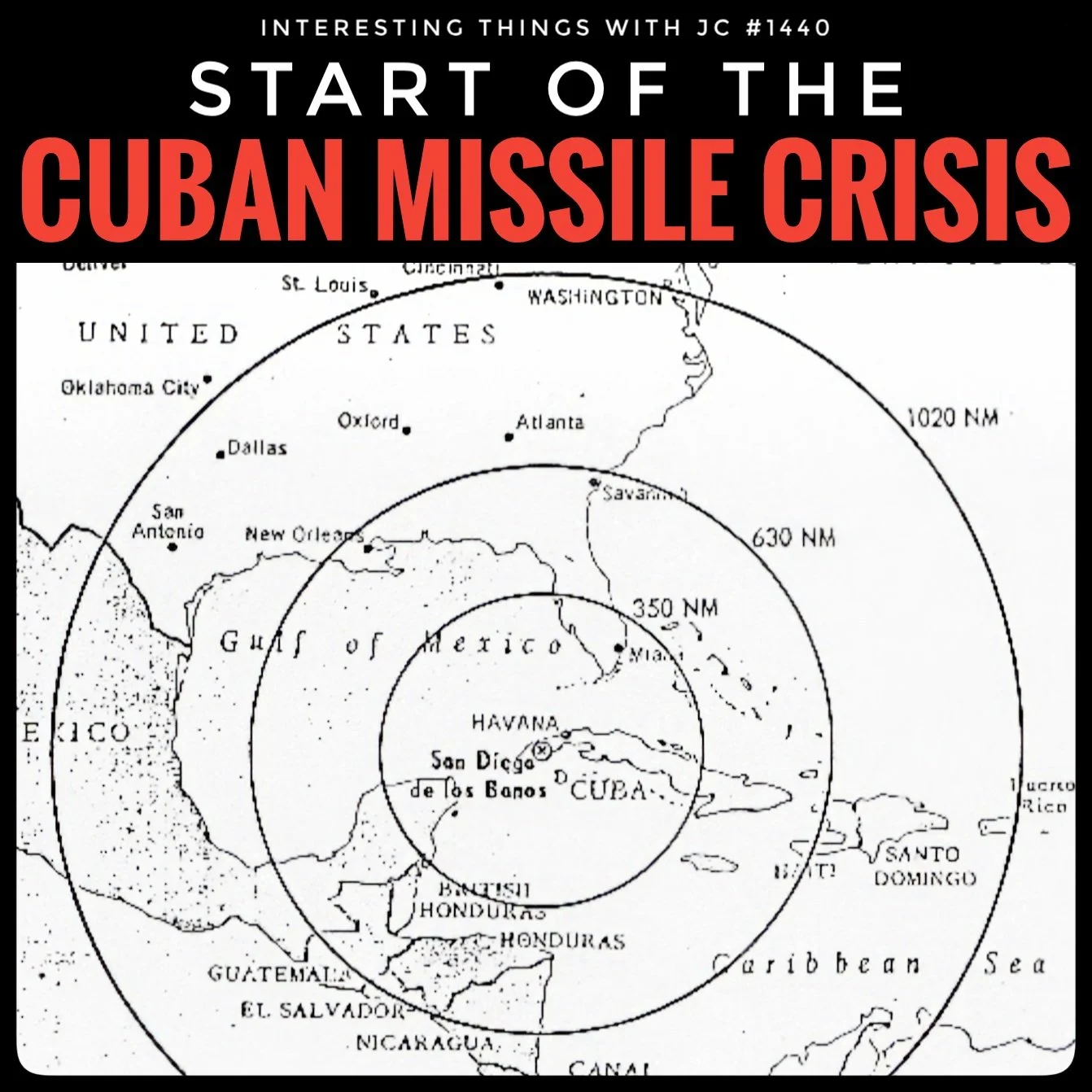

A black-and-white map showing the Gulf of Mexico, the southeastern United States, and the Caribbean during the Cuban Missile Crisis. Three concentric circles centered on Cuba indicate the range of Soviet nuclear missiles, 350 nautical miles, 630 nautical miles, and 1,020 nautical miles, reaching cities like Miami, Dallas, and Washington, D.C. The top of the image reads “Interesting Things with JC #1440: Start of the Cuban Missile Crisis” in white and red text against a black banner.

Transcript

In October 1962, the world nearly ended, and most people didn’t even know it. A U.S. Air Force pilot named Major Richard Heyser (HAY-ser) flew a U2 reconnaissance aircraft more than 70,000 feet (21,300 meters) above western Cuba. From that altitude, the island looked peaceful, green fields and beautiful villages, but the photographs he brought back to Washington showed something else entirely.

In those images were long, narrow launch pads, concrete roads, and cylindrical objects about 60 feet (18.3 meters) long, Soviet R12 medium-range ballistic missiles. Each could carry a nuclear warhead capable of destroying an American city within minutes. The missiles had a range of roughly 1,200 miles (1,930 kilometers), placing Washington D.C., New York, and most of the southeastern United States within reach.

The discovery wasn’t random. U.S. intelligence analysts had watched Soviet freighters unloading “defensive” equipment for months. Those ships carried crates marked as tractors but filled with missile parts. Premier Nikita Khrushchev (kruh-SHCHOFF) wanted parity. The United States had already placed its Jupiter missiles in Turkey and Italy, just 1,500 miles (2,400 kilometers) from Moscow. The Soviets now sought an equal threat, positioned only 90 miles (145 kilometers) from Florida.

When President John F. Kennedy received the photographs on October 16, 1962, he immediately formed a secret advisory group, the Executive Committee of the National Security Council, or ExComm. In that tight circle sat men like Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and General Maxwell Taylor. The tone was sober. For the first time in history, an adversary had stationed nuclear weapons within a short flight of the U.S. mainland.

While leaders debated in Washington, life outside went on as usual. In classrooms, children practiced duck and cover drills beneath their desks. In Miami, radio operators scanned static-filled channels, wondering what the next broadcast might bring. And on October 22, families gathered around black-and-white television sets to hear their president speak.

Kennedy’s address lasted 17 minutes. His words were measured, his expression calm. He announced that the Soviet Union had secretly installed offensive missiles in Cuba and that the United States would impose a “quarantine” around the island, an 800-mile (1,287-kilometer) naval barrier enforced by more than 180 American warships. The word “blockade” was avoided deliberately; under international law, that could mean war.

As the quarantine tightened, twenty Soviet ships approached the line. The U.S. Navy tracked them by radar, sonar, and radio intercepts. For hours, the world waited to see who would yield. One ship stopped just short. Another turned back. The rest slowed and drifted. No missiles were launched. No shots were fired. Yet never had silence felt so dangerous.

Two days later, Khrushchev sent a letter offering to remove the missiles if the U.S. pledged not to invade Cuba. The next day, a second message arrived, harsher, demanding that America also withdraw its Jupiter missiles from Turkey. Inside the White House, ExComm argued which letter to answer. Kennedy chose the first, and through secret channels agreed to the second condition.

On October 28, Khrushchev announced that Soviet missiles would be dismantled. Within six months, the United States removed its weapons from Turkey. The world stepped back from the brink.

Thirteen days of fear, strategy, and restraint had defined the most dangerous standoff in human history. For one Florida mother listening to Kennedy’s speech, it meant something simpler. She wrote in her diary, “I just hope my children get to grow up.”

The Cuban Missile Crisis revealed how fragile peace could be and how much it depends on human reason in the face of fear. It began with one U2 flight, one reel of film, and one moment of courage on both sides that kept the world alive.

These are interesting things, with JC.

Student Worksheet

What type of aircraft did Major Richard Heyser fly, and what did he discover?

Why did the Soviets install missiles in Cuba?

What does the term “quarantine” mean in this historical context, and why wasn’t it called a “blockade”?

Compare the missile placements in Cuba and Turkey—how were they similar or different in terms of threat?

Imagine you are a student in 1962. Write a short journal entry about how you might have felt hearing Kennedy’s speech.

Teacher Guide

Estimated Time: 60–90 minutes

Pre-Teaching Vocabulary Strategy:

Use Frayer models or word walls with historical visuals to clarify Cold War-specific terms (e.g., “ballistic missile,” “quarantine,” “ExComm”).

Anticipated Misconceptions:

Students may think “quarantine” referred to a health-related event.

Some may believe the crisis was only about Cuba, not understanding its global implications.

Discussion Prompts:

How close did the world come to nuclear war in 1962?

Was the U.S. justified in its response to Soviet actions?

How does diplomacy compare to military action in resolving global conflicts?

Differentiation Strategies:

ESL: Provide translated vocabulary sheets or use visuals.

IEP: Offer guided notes or sentence stems for responses.

Gifted: Ask students to create a mini-documentary or alternate history timeline of the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Extension Activities:

Analyze Kennedy’s televised address—compare it with modern political speeches.

Research the role of Robert F. Kennedy in the secret diplomacy channels.

Cross-Curricular Connections:

Physics: Explore how ballistic missiles work.

Ethics: Debate the morality of nuclear deterrence.

Media Literacy: Study Cold War propaganda and media framing.

Quiz

Q1. What did the U-2 reconnaissance photos reveal in Cuba?

A. New agricultural centers

B. Soviet ballistic missile sites

C. Weather stations

D. Refugee camps

Answer: B

Q2. Why was the term “quarantine” used instead of “blockade”?

A. It sounded more serious

B. It was easier to pronounce

C. It avoided legal implications of war

D. It referred to medical precautions

Answer: C

Q3. What was the range of the Soviet R-12 missiles?

A. 500 miles

B. 1,200 miles

C. 2,400 miles

D. 800 miles

Answer: B

Q4. Who led the Executive Committee of the National Security Council during the crisis?

A. Nikita Khrushchev

B. Richard Nixon

C. John Glenn

D. John F. Kennedy

Answer: D

Q5. What did the U.S. secretly agree to remove after the crisis?

A. Nuclear subs

B. Naval ships

C. Jupiter missiles from Turkey

D. Spy satellites

Answer: C

Assessment

In what ways did the Cuban Missile Crisis change the approach to Cold War diplomacy?

How did the actions of individual leaders shape the outcome of the 13-day crisis?

3–2–1 Rubric:

3 = Accurate, complete, thoughtful

2 = Partial or missing detail

1 = Inaccurate or vague

Standards Alignment

U.S. Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.2 — Determine central ideas of a primary or secondary source.

C3.D2.His.14.9-12 — Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

CTE.HSS.9.1 — Evaluate leadership and diplomacy in global conflict resolution.

ISTE 1.3b — Students evaluate the accuracy, perspective, credibility and relevance of information, media, data or other resources.

International Equivalents:

IB MYP Individuals & Societies Criterion B — Investigating historical events using a variety of sources.

UK GCSE Edexcel History Paper 1 — Understanding international relations and the Cold War (1941–91).

Cambridge IGCSE History 0470/13 — International Relations since 1919: The Cuban Missile Crisis.

Show Notes

This episode explores one of the most pivotal moments in 20th-century history: the start of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Through narrative storytelling, JC brings listeners into the tension of October 1962, when nuclear war hung in the balance. The episode highlights key decisions, diplomacy, and restraint that prevented global catastrophe. It’s a powerful tool for teaching students about the Cold War, crisis management, and international relations. In today’s world of rising geopolitical tensions, this episode remains profoundly relevant for teaching how fragile peace can be, and how diplomacy and leadership can determine the course of history.

References:

Fursenko, A., & Naftali, T. (1997). One Hell of a Gamble: Khrushchev, Castro, and Kennedy, 1958–1964. W. W. Norton. https://archive.org/details/onehellofgamblek00furs

National Archives. (n.d.). The Cuban Missile Crisis, October 1962. https://www.archives.gov/research/foreign-policy/cuban-missile-crisis

JFK Library. (n.d.). The Cuban Missile Crisis. https://www.jfklibrary.org/learn/about-jfk/jfk-in-history/the-cuban-missile-crisis

U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). Office of the Historian: The Cuban Missile Crisis, October 1962. https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/cuban-missile-crisis

Connors, J. (n.d.). Dad: The Original JC. JimConnors.net. https://jimconnors.net/dad-the-original-jc