1532: "Wasabi or Horseradish?"

Interesting Things with JC #1532: "Wasabi or Horseradish?" – That green stuff next to your sushi? It’s not wasabi. It just looks the part. The real thing is rare, pricey, and totally different. You’ll taste the truth.

Curriculum - Episode Anchor

Food science, plant biology, and consumer literacy intersect in this episode by revealing how appearance, chemistry, agriculture, and economics shape what people believe they are eating.

Episode Title: Wasabi or Horseradish?

Episode Number: 1532

Host: JC

Audience: Grades 9–12, college intro, homeschool, lifelong learners

Subject Area: Biology, Food Science, Consumer Literacy, Cultural Studies

Lesson Overview

This lesson examines the biological, chemical, agricultural, and economic differences between real wasabi and horseradish-based substitutes. Students analyze why substitution occurs, how plant chemistry affects flavor, and how labeling practices influence consumer understanding.

Learning Objectives

Students will be able to:

Define the biological differences between Wasabia japonica and horseradish.

Compare the chemical compounds responsible for heat and flavor in wasabi and horseradish.

Analyze how environmental growing conditions affect agricultural cost and availability.

Explain why most products labeled “wasabi” are substitutes rather than authentic wasabi.

Key Vocabulary

Wasabia japonica (wah-SAH-bee-ah jah-POHN-ih-kah) — The plant species that produces authentic wasabi, grown in cool, flowing mountain streams.

Rhizome (RY-zohm) — An underground plant stem that grows horizontally and produces roots and shoots; the edible part of real wasabi.

Horseradish (HORSE-rad-ish) — A fast-growing root plant related to mustard, commonly used as a wasabi substitute.

Mustard oils (MUS-tard OY-uhlz) — Chemical compounds called isothiocyanates that create heat and pungency when plant cells are crushed.

Substitution (sub-stih-TOO-shun) — The replacement of one product with another due to cost, availability, or practicality.

Narrative Core

Open: The familiar green paste beside sushi triggers intense heat and watering eyes, immediately engaging curiosity about its true identity.

Info: Wasabi and horseradish come from the same plant family and share chemical compounds, but they grow differently and behave differently on the palate.

Details: Authentic wasabi requires rare environmental conditions, years to mature, and loses flavor quickly, while horseradish is cheap, durable, and easy to mass-produce.

Reflection: The episode reveals how convenience, economics, and consumer assumptions shape everyday experiences with food.

Closing: These are interesting things, with JC.

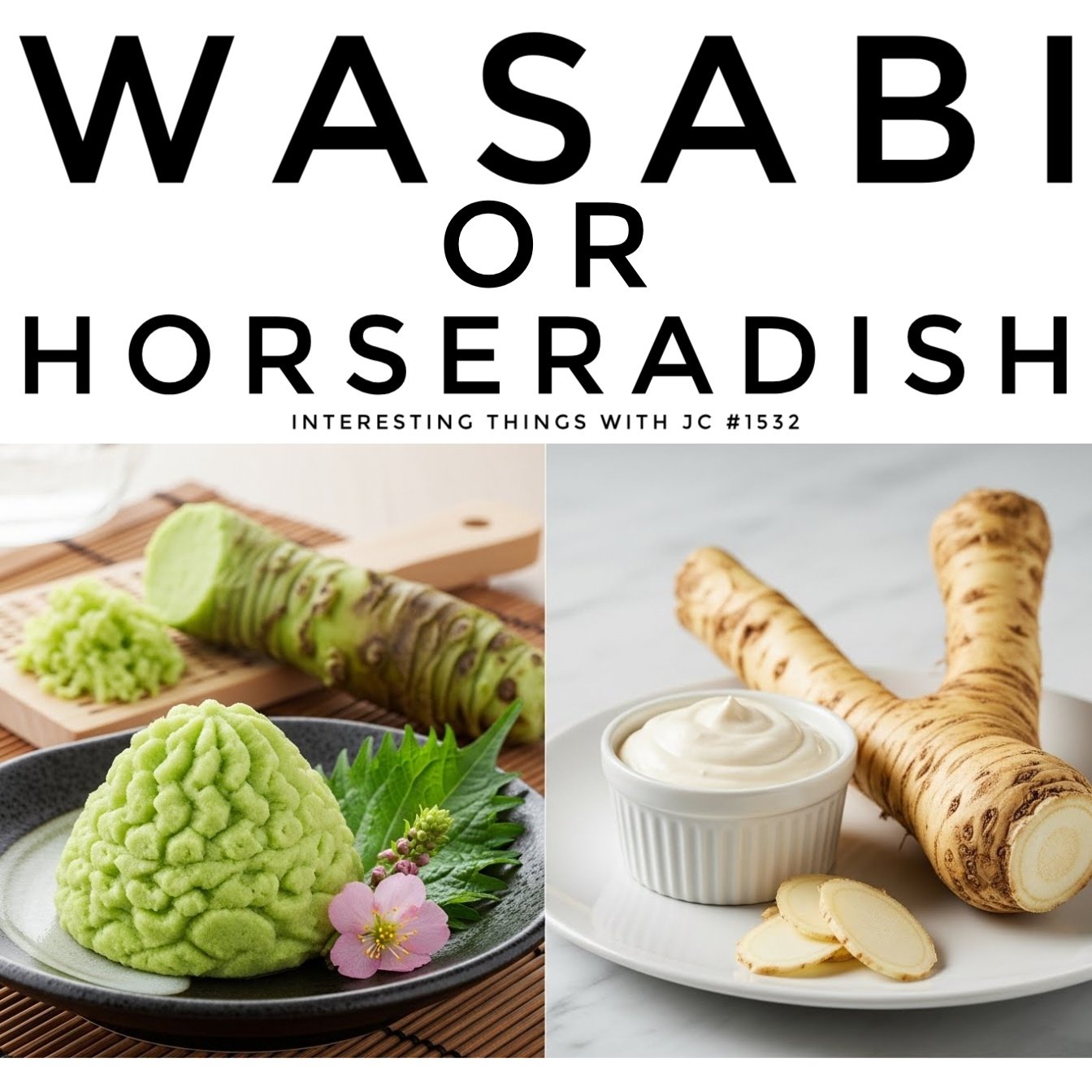

Promotional graphic titled “Wasabi or Horseradish?” showing real grated wasabi and wasabi root on the left, and horseradish root with cream sauce on the right, comparing the two ingredients visually.

Transcript

Interesting Things with JC #1532: "Wasabi or Horseradish?"

That green blob next to your sushi? The one that blasts your nose and makes your eyes water?

It isn’t wasabi.

It’s almost always horseradish. Mixed with mustard powder, starch, and green coloring. Looks right, burns hot, but it’s not the real thing.

Real wasabi comes from a plant called Wasabia japonica. It grows in cold, shaded mountain streams in Japan. The part we eat is the underground stem, called a rhizome. It’s in the same family as horseradish and mustard, but it’s slow to grow. It needs clear, flowing water, cool weather, and years to mature. Fresh wasabi can cost over three hundred dollars per kilogram—about one hundred thirty-five dollars per pound.

Horseradish, by contrast, grows fast in ordinary soil. It’s a hardy root crop, easy to harvest, and much cheaper. When grated, it gives off a strong heat from the same chemical group—mustard oils—but the flavor hits harder and lasts longer.

That’s why it took over. It’s reliable. It stores well. And when mixed with green dye, most people can’t tell the difference.

But the flavor’s not the same.

Horseradish burns. It lingers. It stings the nose and sticks around. Real wasabi rises gently, fades fast, and tastes sweet and herbal. No shock. Just lift.

Even in Japan, most sushi spots use the fake stuff. The real thing is reserved for high-end counters. It’s grated fresh, right before serving, because it starts losing flavor after fifteen minutes.

A few farms outside Japan grow it now—in Oregon, British Columbia, and New Zealand—but supply is tiny. Demand isn’t.

Most products labeled “wasabi” only contain a trace. Just enough to use the name. The rest is filler.

So if yours came in a packet or a tube, you’ve probably never had the real thing.

But if you ever do, you’ll know.

These are interesting things, with JC.

Student Worksheet

Explain why real wasabi is difficult and expensive to produce.

Describe how the flavor experience of horseradish differs from real wasabi.

Why does horseradish make a practical substitute from a business perspective?

How does this episode change the way you think about food labeling?

Teacher Guide

Estimated Time

One 45–60 minute class period

Pre-Teaching Vocabulary Strategy

Introduce rhizome, mustard oils, and substitution using labeled plant diagrams and real-world food examples.

Anticipated Misconceptions

All green paste labeled wasabi is authentic

Stronger heat means higher quality

All plant roots grow the same way

Discussion Prompts

Why do consumers often accept substitutes without realizing it?

Is substitution misleading, or is it practical?

How should foods be labeled to balance accuracy and cost?

Differentiation Strategies

ESL: Visual plant diagrams and sentence frames

IEP: Guided notes and simplified vocabulary lists

Gifted: Independent research on specialty crop economics

Extension Activities

Compare wasabi substitution to vanilla, olive oil, or truffle products

Create a consumer awareness infographic

Research how flavor chemistry affects perception

Cross-Curricular Connections

Chemistry: Chemical reactions in crushed plant cells

Geography: Climate requirements for specialty crops

Economics: Supply, demand, and pricing of rare foods

Quiz

Q1. What part of the wasabi plant is eaten?

A. Leaf

B. Flower

C. Rhizome

D. Seed

Answer: C

Q2. Why is real wasabi expensive?

A. It grows only in laboratories

B. It requires specific environmental conditions

C. It must be imported frozen

D. It is genetically modified

Answer: B

Q3. What chemical group causes the heat in both wasabi and horseradish?

A. Capsaicins

B. Sugars

C. Mustard oils

D. Acids

Answer: C

Q4. Why does real wasabi lose flavor quickly?

A. It evaporates

B. The compounds break down after grating

C. It dries instantly

D. It cools too fast

Answer: B

Q5. Most commercial “wasabi” contains mainly:

A. Wasabi root

B. Ginger

C. Horseradish

D. Chili pepper

Answer: C

Assessment

Open-Ended Questions

Explain how biology and economics together explain why horseradish replaced wasabi.

Analyze how consumer expectations influence food production choices.

3–2–1 Rubric

3 = Accurate, complete, thoughtful explanation

2 = Partial understanding with missing detail

1 = Inaccurate or vague response

Standards Alignment

NGSS

MS-PS1-3 — Chemical properties and practical use

HS-LS1-1 — Structure and function of biological systems

Common Core Literacy

RST.9-10.1 — Cite evidence from scientific texts

RST.9-10.2 — Determine central ideas

C3 Framework

D2.Geo.2.9-12 — Human-environment interaction

D2.Eco.1.9-12 — Economic decision-making

International Equivalents

UK National Curriculum Science KS4 — Chemical properties of materials

IB MYP Sciences — Structure, function, and sustainability of biological systems

Cambridge IGCSE Biology — Plant structure and adaptation

Show Notes

This episode explores the surprising truth behind one of the most familiar foods served with sushi. By examining plant biology, chemistry, and agricultural economics, it reveals how horseradish became a stand-in for real wasabi. The topic connects directly to classroom discussions about food labeling, consumer awareness, and how environmental constraints shape global cuisine. Understanding this distinction encourages students to think critically about what they consume and why substitutions are common in modern food systems.

References

Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. (2024). Wasabi. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/wasabi

FoodStruct. (2024). Horseradish vs. wasabi — Differences and similarities. https://foodstruct.com/nutrition-comparison-text/horseradish-vs-wasabi-root-raw

Real Wasabi, LLC. (n.d.). Wasabi cultivation and growing conditions. https://realwasabi.com/pages/cultivation-index-asp

Specialty Produce. (n.d.). Wasabi root. https://specialtyproduce.com/produce/Wasabi_Root_756.php

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. (2022). Food labeling: Flavorings and color additives. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition